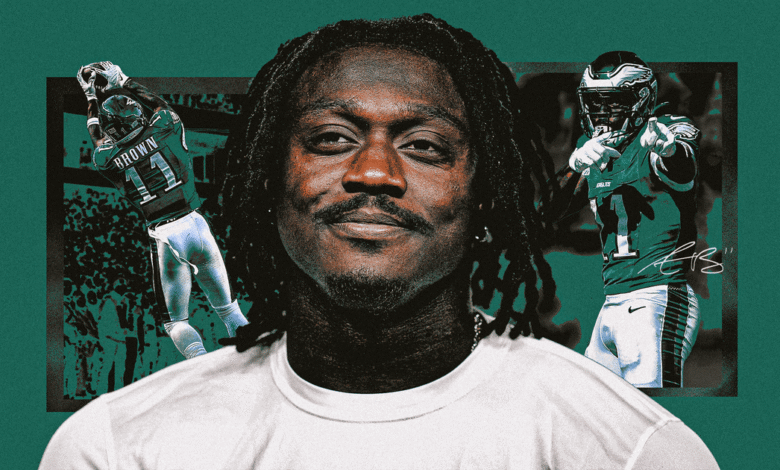

What does A.J. Brown want? Eagles’ star WR chases greatness — on his terms

Away from pinging phones, away from all the red-alert headlines, A.J. Brown is at his locker. There’s no need here to decode his social media posts or deduce what reports are true. He’s talking about what actually matters to him.

He’s talking about why catching the football is existential for him. He’s talking about why a cathartic expression flashed beneath his trademark visor during a fourth-quarter sequence in which he broke three tackles on a go-ahead drive against the Los Angeles Rams.

“I know everybody’s counting on me — that’s my thrill,” Brown tells The Athletic. “And then I come through. That makes me proud of myself. And I’m doing it over and over again. And then I got another opportunity a couple of plays later. Third down. Everybody knows the ball’s coming to me. I love that feeling. Like, it’s a rush. I don’t do drugs, but that has to be what drugs feels like. And I’m getting that dopamine. And I’m coming through for my team again.

“And that’s where the excitement comes from. And that’s why it’s frustrating at times. And maybe people really misunderstand me as a player, but those feelings — that’s what I want. You may see a little frustration. It’s because I really want to contribute. I really want to help this team win. But if I’m not getting the ball, obviously, it’s not as fun.

“Obviously, I want to win. That’s the main goal. But I want to help. I want to do my thing as well. And so it’s a little toll here and there sometimes. But I think that’s where the misunderstanding comes from, from everyone out there. But to be honest, I could really care less. This got me here. You know? And me playing this way, me having that drive, me having that mindset — it’s going to keep me here.”

Here is not a physical place. That’s worth remembering when the bulk of Brown’s world deals in those terms. Brown defined his destination back in training camp, back when he paused for 13 seconds before answering what was left for a three-time All-Pro wide receiver and Super Bowl LIX champion to accomplish.

“Being the best version of myself,” he said.

Anyone who has watched the Philadelphia Eagles since the franchise traded for Brown in 2022 has seen that version taking form. They saw how Brown immediately set the team’s single-season record for receiving yards. They saw Brown’s NFL-record streak of six 125-yard games in 2023. They saw Brown’s third straight 1,000-yard season in 2024, with touchdowns in Sao Paulo and the Super Bowl. They have seen what it means for Brown to exist.

But when the catches stop coming, so do their meaning.

It is why it so often feels like Brown is talking about two things at once, why Brown sometimes avoids reporters after games; they must ask about the system, the plays, the wins, the losses; he must first confront the emotions, the confines, the contingencies beyond his control. It is also why Brown’s vented frustrations often lack a clear target, why his self-absorbed social media posts should be consumed with caution.

On Sept. 28, after the Eagles survived a near-comeback by the Tampa Bay Buccaneers despite clunky offensive play, Brown, who was targeted nine times but had just two catches for 7 yards, steered clear of reporters to sort out his feelings. He opened his phone and found a screenshot of a post featuring a verse from the Gospels — “If you’re not welcomed, not listened to, quietly withdraw. Don’t make a scene. Shrug your shoulders and be on your way” — along with a caption calling God, “the only one we should ever concern ourselves with.”

Brown uploaded the post to social media and fired away. “It’s not directed at anyone,” he told reporters days later.

After Brown’s two touchdown catches helped beat the Minnesota Vikings on Oct. 19, he fired another social media salvo. “Using me but not using me,” he posted, along with an attached video of a local bodybuilder he trained with shouting, “I’m built different. I train different. I work different. I am different. … The work ain’t done till it’s done, motherf—er.”

Brown hasn’t spoken with reporters since. He missed all three of last week’s practices with a hamstring injury and was sidelined in Sunday’s win over the New York Giants. His teammates decline to interpret his posts.

Quarterback Jalen Hurts: “I just keep my focus singularly on the collective.”

Wide receiver DeVonta Smith: “It’s none of my business.”

Few stars are as open about their feelings as Brown. Fewer are as willing to speak about how their sense of self gets snarled with the desire to be truly seen. Public opinion only serves as a multiplier of things he already feels. “Athletes deal with it all the time,” he said.

It is why a crowd’s roar boosts him when the ball’s in his hands, why some boos miss and others sting. It is also why Brown tries to remember there is no other measurement of greatness than his own.

Brown didn’t let just anyone live with him at Ole Miss. He told Elijah Moore as much through tears on the day Moore was drafted.

Moore had the charisma of a preacher, the resolve of an apostle and a football fanaticism only Brown matched. DK Metcalf still laughs when he talks about picking Moore up for his official visit to Ole Miss. After Moore asked Metcalf how he felt about football, and after Metcalf confided that he was trying to love it more, Moore looked at him and said, “Hey bro, drop me off at A.J.’s.”

“They always took it very seriously,” Metcalf said.

DK Metcalf and A.J. Brown went from high school rivals to college teammates at Ole Miss. (Clarion Ledger / USA Today Network via Imagn Images)

So does he … now. A two-time Pro Bowler for the Seattle Seahawks, Metcalf is currently the leading receiver for the Pittsburgh Steelers. Back then, he was the son of a former NFL lineman still sorting out his own desire for the game.

Brown awakened a fire in Metcalf. They’d attended rival high schools in Mississippi. They became brotherly competitors. When a coach set them against each other in an Oklahoma drill, they stalemated for two seconds, then Brown got under Metcalf and drove him back. Metcalf vowed never to let it happen again.

When Metcalf threw 315 pounds on the bench press and lifted it, Brown threw on 320, benched it, then looked at Metcalf, provoking him to bench it himself. When their strength coach held a pull-up challenge with weighted vests, everyone else bowed out before 30. Metcalf and Brown kept staring each other down, daring the other to quit.

“We couldn’t think about, ‘Oh, my arm’s hurting,’” Metcalf said. “It was, ‘I beat A.J. today.’ Or, ‘A.J. beat me today.’ That was it. ‘Cause we knew we were going to be the best at whatever we did. We didn’t let either one of us outdo the other one.

“Without A.J., I don’t think I’d be the player that I am.”

At Ole Miss, they learned “what this sh– feel like,” in Metcalf’s words, when they’d worked hard. Metcalf and Moore both remember 10 p.m. calls from Brown about extra workouts. They’d swipe the key card from their receivers coach, unlock the indoor practice facility, drag out the JUGS machine and crank up the facility’s speakers. They’d head to the sand volleyball court for footwork drills. They’d grab food, return to one of their apartments and reverse-engineer highlight videos of NFL All-Pros Antonio Brown and Julio Jones.

Jones was Brown’s childhood hero, his reason for playing wide receiver, his former teammate for two partial seasons in Tennessee and Philadelphia in 2021 and 2023, respectively. Brown still watches Jones’ highlights before games. As Brown said in a 2023 interview, “Julio taught me everything I knew without talking to me.”

By the time his image-bearer was brought into the same locker room, Brown had already established the habits of the future Hall of Famer he wanted to become. Eagles left tackle Jordan Mailata said Brown spends more time in their training room than anyone, working on “the smallest stuff that you wouldn’t even think about.” Resistance bands for minor muscles. Balance exercises. Refining jukes for his routes. Fellow receiver Britain Covey said Brown’s research runs to the bottom of an opponent’s depth chart.

Work supplies Brown’s confidence. Catches supply Brown’s confirmation. He said God showed him he could be the “best in the league” on Sept. 8, 2019, when, as a rookie for the Tennessee Titans, he caught three passes for 100 yards against the Cleveland Browns after feeling the rush of an opposing crowd roaring during the introductions of Odell Beckham Jr. and Jarvis Landry.

“Most guys just play the game and just accept whatever comes with it,” Brown told The Athletic. “I could care less about that. It’s about me being the best and me proving that to myself over and over again, each and every day. That’s why I work so hard. That’s why I try to get ahead, take advantage of opportunities and have the mindset each and every day and play with the tenacity that I play with.”

Moore, now with the Buffalo Bills, said if anybody saw how Brown functions, they’d “be impressed with his daily living (reading habits, diet, parenting) before they would be impressed with anything about how that dude plays football.” During their Ole Miss days, Moore said Brown encouraged him by repeating a saying: “Pick your Hard,” which fits perfectly with football. Good games and bad games. Good plays and bad ones. It’s life. It’s hard.

Brown has racked up 28 touchdown catches since coming to Philadelphia ahead of the 2022 season. (Mitchell Leff / Getty Images)

Brown has discovered that his daily discipline is more fulfilling than the goals he’s pursued. After the emotional high of Super Bowl LIX wore off, Brown posted a candid message on Instagram about how he’d thought being a champion would justify all of his work — and how it surprisingly didn’t.

“I tried to embrace the feeling of what I thought it would be,” Brown told The Athletic. “Because when I got to the league, we just got placed with the expectation, ‘This is what we play for.’ And it kind of taught you how to feel in a way. And when we won, it was like I was trying to feel it, right? But it wasn’t that.

“I kind of stole that moment from myself. And so I didn’t experience that the right way. … I think when you place expectations on something, you’re really stealing your own feeling from it because you want something to be something, and you have no idea what it’s going to be like. And that’s exactly what I did.”

Beyond the 165-acre property where a young A.J. Brown once pitched crab apples like baseballs and dragged a tire through the dirt, beyond the skeet-shooting fields and lightning-bug lands, the faithful rest their feet on the plum-colored carpet beneath the wooden pews of 16th Section Missionary Baptist Church.

This is where Arthur Juan Brown stood as his two older sisters sang in the choir. It’s where he sat with his father, Arthur “Bug” Brown, and mother, Josette Robertson, before they divorced when he was about 12. When his mother moved away, A.J. decided to stay with his father in Starkville, Miss.

Brown described his dad as “a disciplinarian.” Bug didn’t spare the belt and didn’t spoil his child. Bug set his son’s eyes on opportunities but withheld the nurturing that would’ve made A.J. feel worthy, lest positivity distract him. Bug worked for Starkville’s electrical department, constructed a makeshift training complex in a backyard that included a batting tee and basketball hoop and was A.J.’s sharpest critic from the stands — even after A.J.’s best games.

Stay focused, Bug always said. As a kid, A.J. hated hearing that. “I was looking for an, ‘I’m proud of you,’” he said. He thought his father was just trying to stop him from having fun. But Bug still tells his son to stay focused today. A.J. understands now that his father was teaching him discipline, something he believes took him farther than nurturing ever could.

Still, A.J. longed for affirmation growing up. In his commencement speech at Ole Miss last year, he urged graduates to “be that person you needed when you were younger.” So who did younger A.J. need? “Somebody to look up to other than my father,” he said. He needed “a mentor,” someone with “a different perspective.” He needed a hero to visit his section of Starkville and tell him, “whatever you want to achieve, you can really achieve it.” And to show him the way.

In a May visit to the Delaware County Juvenile Detention Center just southwest of Philadelphia, Brown told a group of teenagers his parents’ split still affected him. He “acted out” and “did stupid stuff.” He failed the seventh grade because he was pursuing attention from his parents. He developed trust issues that still pervade the relationships he forms today.

He drew a distinction between teammates and friends. The game gives him comrades in ample supply, although he questions who’ll still be there when the curtain falls. But friends? He held up two fingers and crossed them. No. He doesn’t have those.

“When it comes to friends, for me, that’s a tough subject,” Brown said. “Obviously, I have teammates who I care about and I love. But as far as close friends who I can truly, truly depend on, I think that’s just a lot. And I don’t want to place that on someone.”

Why?

“I just feel like I would never want to place things that I go through on someone else,” he said.

“A.J. is particular,” said Moore, perhaps the closest person to embodying both categories. “When you call someone a friend, it’s like basically one level below a wife: a true friend. A friend that’s seen everything, all your flaws, not going to judge you but also work through them with you.”

Brown has long been an advocate of personal wellness. His 2024-launched A.J. Brown Foundation promotes programs for young people. He partnered with clothing brand Peace Collective to launch a collection on Oct. 10, World Mental Health Day. In 2021, Brown revealed that he’d contemplated taking his own life in November 2020. He called Moore, among others, to help get through the experience. Their shared faith shields them from a fear they only described in general terms. Fear itself, Moore said, is a feeling that “comes from the evil one.” Since it is not from God, they can let it go.

This year, Brown hung a new poster inside his locker. It’s an enlarged receipt. The itemized list: Sin, Shame, Pain, Past Mistakes. The balance is zero. The top of the poster reads, “Jesus Paid It All.” Brown is sometimes quiet about his faith. He said he had the poster in his car for “a couple weeks” before he brought it inside. He hopes people watching his weekly interviews will spot the receipt over his right shoulder. “It may save their life,” he said, “save their soul.”

Brown tries to “turn to Jesus” in both his reading and prayer and unload all the things he never trusted anyone could handle during his formative years. It became a discipline.

A nurturer, or a mentor, would have given a younger A.J. motivation, doses of the self-belief he so often lacked. But such doses wear off, he reflects, leaving him alone with his discipline.

“Motivation really doesn’t even exist. It’s not even real,” Brown said. “One day, you can be motivated. The next day, you’re not. But if you’re disciplined, you do it every day, regardless of the feeling that you have, it’ll take you way further than motivation ever will. It’s rare times that you’re motivated. But even when you’re motivated, that’s like a small glimpse of what you feel like you can become. When that motivation does come around in your discipline, that’s the best feeling in the world.”

A.J. Brown Jr. knows when it’s time to have a talk with his father.

The toddler just turned 3, but he’s gotten a hang of their routine. The father sits his son down near the couch, or near the kitchen, or near the toys. The father speaks slowly, solemnly. The son nods his head.

“OK, Da-Da. OK.”

A.J. Brown wonders how much of their talks his son actually retains, but he resolved to level with his son about life as soon as possible.

And something has happened as Brown spoke to his son: He listened to his own words. Where was this advice coming from? It was good advice. It was what he’d needed to hear. So, Brown started taking his own advice. It expanded their interactions. Sure, Brown doesn’t want his son to make the wrong choices. But that nodding, it’s like the toddler telling his father he’s going to be all right, too.

“OK, Da-Da. OK.”

On MLB’s Opening Day earlier this year, Brown posted a video in which he asked Junior if he wanted to play baseball. “Yeah,” the 2-year-old jabbered … until Brown told him he’d have to tell his mother goodbye to commit to the grind. Junior started crying. Brown’s fiancée, Kelsey, scolded him off camera. Brown laughed and kissed his son.

“Let’s just say… He won’t be playing baseball,” Brown wrote in the caption.

The grind hurts. Brown, a former All-American high school center fielder whom the San Diego Padres drafted in 2016, said he chose football over baseball partly because he was apprehensive about being isolated in a grueling minor league system. Brown also had an offer to play football at Alabama, the alma mater of Julio Jones, but said he was intimidated by the reigning national champion’s star-studded roster and its No. 1-ranked recruiting class. He signed with Ole Miss instead.

The irony of it all is that Brown tried to avoid tough journeys in baseball and ‘Bama — but fell into one anyway.

“I’m human, too,” Brown said. “I didn’t know how to push past that. And I kind of avoided that. And I still ran into a situation where I had to stay patient. I still ran into a great recruiting class at Ole Miss. And I still had to wait for my turn. But it taught me in that moment of waiting, focusing on myself, focusing on my process, my journey.”

Brown delivered the commencement address at his alma mater in May. (Bruce Newman / Special to the Clarion Ledger / USA Today Network via Imagn Images)

Brown is two years away from the start of the three-year, $96 million extension that’s scheduled to keep him in Philadelphia through the 2029 season. Eagles GM Howie Roseman’s acquisition and retention of Brown ended the organization’s decade-long search for exceptional wide receivers. Coach Nick Sirianni has often called Brown the greatest wide receiver in Eagles history. Yet speculation persists about whether or not Brown will stay in Philadelphia through the end of his contract.

Brown avoided cameras to dampen narratives in 2023 but broke his weeks-long silence when conjecture only intensified. When the rumor mill reached a fever pitch during the 2024 offseason, Brown called into the WIP-FM afternoon show to squelch theories that things weren’t so sunny. “I want to be here — simple as that,” Brown said during the nearly 20-minute call. He signed his contract extension two months later.

Outsiders remain unconvinced. Among them, NFL decision-makers. An AFC general manager told The Athletic’s Dianna Russini earlier this month that it wouldn’t surprise him if the Eagles moved Brown before next-week’s trade deadline. Onlooking executives are catching on to Brown’s existentialism and wondering whether it can be managed in Philadelphia.

But it is fair to question how any other team would be better equipped when it’s the game itself that creates Brown’s confines.

Brown has long bristled at how wide receivers are so easily labeled “divas.” Indeed, it is arguably the position in football that deals with the most contingencies. For all the All-Pros who were labeled high-maintenance — Keyshawn Johnson, Terrell Owens, Chad Johnson, et. al — could they not at the very least be understood for being squeaky wheels inside of a conditional structure?

“So much stuff has to happen in order for us to get the ball,” Metcalf said. “Even when you’re waking up at five in the morning during the offseason and working your butt off, and you come in training camp and during the season, and you’re in top shape and you’re catching everything, you know how to get open, you know the playbook. It’s still contingent on the quarterback gotta see you, the o-line gotta hold their block, you got to know your route and run your route full speed, and hopefully the quarterback can see you and throw a good ball.

“So, you just have to know this is the ultimate team game and no matter how hard you work, you’ve still got to depend on everyone else.”

Brown understands football’s structure. Two sentences after stating in training camp that he wanted to put a stamp on his season, he added, “Also, I have to put the team first.” The dynamic inherently creates a short list of decision-makers Brown can address if he advocates for himself: the quarterback, the play-caller, the head coach. Owners and general managers step in when that flow-chart fails.

Speculation skyrocketed last December when Eagles edge rusher Brandon Graham stoked flames beneath Brown and Hurts on his weekly radio show by saying the pair were friends, “but things have changed.” There may be truth within what Graham said — Brown told Eagles superfan Gillie Da Kid in a February podcast, “Some reports are true, some of them reports aren’t true,” when asked about his relationship with Hurts — but since then, both Brown and Hurts have many times said that their professional goals are aligned. Brown described themselves in the podcast as “two alphas who want to be the best and demand greatness from each other and everyone around us.”

In football terms, Brown and Hurts are intrinsically connected — just like the generations of quarterbacks and wide receivers before them. If Brown’s production wanes, Hurts’ influence cannot be ignored. Nor can first-time offensive coordinator Kevin Patullo’s. Nor Sirianni’s.

Sirianni got emotional speaking about Brown after the Rams game. The fifth-year coach, a former wide receiver himself, said Brown had showcased mental toughness by handling “himself with a lot of maturity” while facing questions about his role in the offense. Patullo acknowledged a wide receiver’s dependency on targets makes them different to manage. Hurts, when asked about how he cultivates his relationship with Brown given the inherent nature of his position, emphasized the collective.

“The main focus is going out there, playing team offense, being on the same page and striving to do that,” Hurts said. “And when you desire to play team offense, you’ve got to understand that everyone has an impact on every lasting play.”

A sign has long hung above Brown’s locker. It reads “Always Open.” Eagles running back Saquon Barkley reminded a reporter that “it’s the truth” after Brown’s season-best game against the Vikings. But Brown knows he must balance his pursuit of personal fulfillment within a game he’s often acknowledged is a team sport.

Brown is in his third straight year as a team captain. Mailata described him as “a total pro,” a leader who is known differently behind the scenes than how he is often portrayed. Second-year nickel Cooper DeJean, who’s often seen shadow-boxing with Brown in practice or chatting along the sideline, called Brown “a great mentor,” someone who’s “taught me a lot, not only about football, but about life and how to handle the ups and downs of everything.”

“Me being close to him, I think it’s helped me,” DeJean said. “Just having that confidence in myself, playing like you think you’re one of the best in the league. It gives you confidence on game day to just go out there and be yourself. As long as you’re yourself and you have that confidence in yourself, everything’s gonna be all right.”

Perhaps the more Brown speaks to his teammates, the more he listens to his own advice, too. Perhaps it’s also what he needs to hear.

Source link