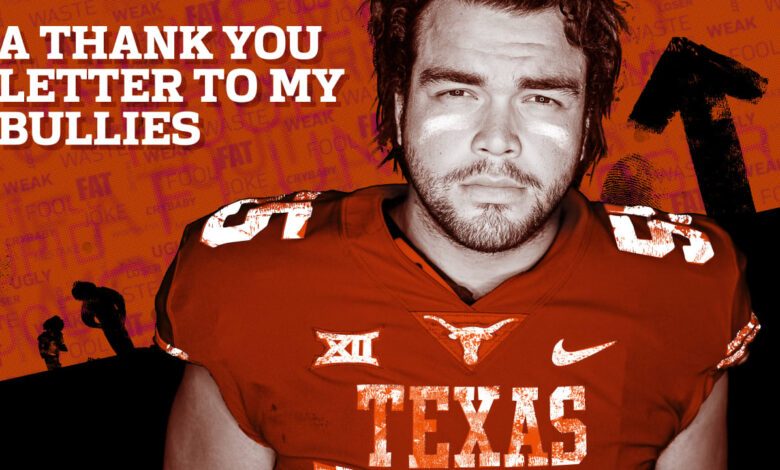

Connor Williams has nothing but gratitude for his childhood tormentors

I remember always thinking how great it would be to hang out with the “cool” kids. I used to ask some of you if I could join your group for an activity, and the answer was always the same: No!

You had no idea how much that broke my heart. As humans, we have a need for companionship. And I was left alone. All alone.

I loved football. With my size, the game my dad and brother, Dalton, played in college seemed like a natural fit. But you even tried to take that away from me.

Remember in fourth grade how you held drafts to pick teams? And how every time I was still sitting there at the last pick, humiliated knowing I would be left only to watch? You said I couldn’t contribute and told me I couldn’t play. So I just watched. I watched and I watched until I stopped watching altogether.

I was tired of getting hurt. The pain of going through the picks and knowing I would be last, knowing I would be the odd man out was too much to bear. After a while I was like, “This is crap.” So I started walking the track every day instead of going through that humiliation.

I’m sure you never noticed.

I grew angrier with every lap. Anger from how badly I wanted to be different, how I wanted to change. How I wanted people to look at me differently. How I wanted to be liked.

You said I was the problem. The tragedy is, I believed it.

You even had the talent to take the smallest joys I had and turn them into sorrow. Remember that cool eraser I had in middle school, the round, floppy one? Remember how you pretended you liked it, too, and asked if you could see it while boarding the school bus? Perhaps not. But surely you recall what you said:

“It looks like a piece of ham. Eat it, fatty.”

It got me so angry I fought back. And who ended up getting in trouble? Actually, we both did that time, but usually it was just me, the big, fat kid.

The school system teaches you to not retaliate, to walk away. In this instance, I got in trouble for standing up for myself. No wonder more than 67 percent of students believe schools respond poorly to bullying and that 1 in 4 teachers see nothing wrong with bullying and will intervene only 4 percent of the time.

I can’t begin to count the times I came home from school crying. At night, I used to lie in bed, almost like a prayer, wishing I could change. Wishing YOU could change the way you saw me. Saw me like my parents did.

My mom and dad had very different approaches to my situation. Dad and I went to dinner and the movies every Saturday night and we’d even sneak a movie date in during the week if we could. He was always the person I could turn to. If plans fell through – and thanks to you, they usually did – he’d always be there, ready to go to the movies with me.

They were much more than movie dates, however; they were therapy sessions. We shared everything. He listened to me, he understood me. He even allowed me to call him Jimmy. And Jimmy knew it was what I needed to go through to be the man I was becoming.

My mom, on the other hand, wanted to fight my fights for me. What can I say, she’s a mom, and as a Mexican-American, it was a double whammy. Don’t mess with Latin mothers.

I felt her pain because she felt mine. She was a caring mother who didn’t know what to do. It was a growth opportunity for her as well. She’d pick me up from school each day and always knew instinctively what kind of hell I had been through. She’d talk to me about it and I’d talk to her.

They were the people who helped me through my darkest times. My relationship with them is unbreakable.

They took the time to know their youngest son, but you never did. And there were plenty of opportunities.

Like the time in sixth grade when you invited me over to play airsoft wars in the backyard of one of your homes, with acres of open land near the creek. But all the fun ended when you took my pellet gun, pushed me to the ground, and started shooting at me until I cried.

Or the time two of you invited me for a sleepover in middle school, pretending to befriend me, only to beat me up, forcing my parents to come get me in the middle of the night.

Speaking of middle school, remember all the rules? I remember one in particular: Only seven to a table in the cafeteria. I was always the fourth or fifth one at the table but when the guys from the football team wanted to sit down, I knew what was going to happen because it always did, kind of like Groundhog Day. The principal would come by and say, “You’ve got eight, you have to kick someone out.” And I was always the one who got kicked out.

I was embarrassed to sit by myself at another table, so I ate in the library.

Source link