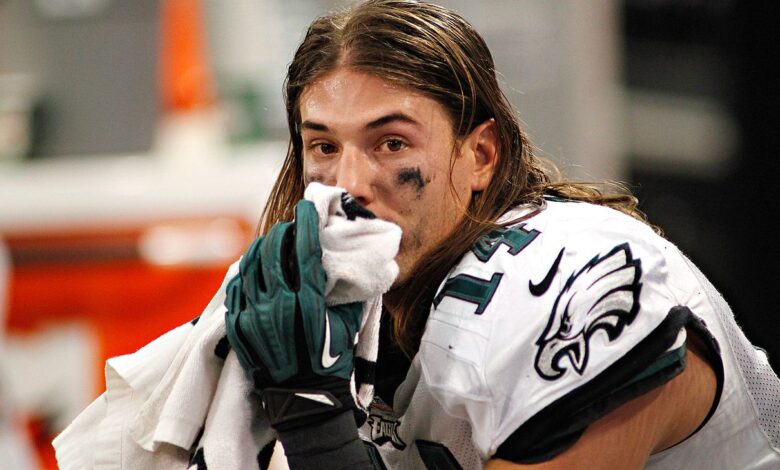

NFL Hot Read — How Riley Cooper put slur in past

There was already some racial tension. Two weeks earlier in Florida, George Zimmerman was acquitted in his murder trial for the shooting of black teenager Trayvon Martin. Four months before that, Philadelphia magazine ran a controversial essay called “Being White in Philly” that rankled Mayor Nutter so deeply that he called for the magazine to be punished over the story.

Sensing the magnitude of the situation, the Eagles also reached out to sports sociologist Harry Edwards.

Edwards, who works with the San Francisco 49ers, is a former Black Panther who helped inspire Tommie Smith and John Carlos to raise their fists during their medal ceremony at the 1968 Summer Olympics. He’d worked with Kelly’s staff before when Kelly was at Oregon and running back LeGarrette Blount punched a white Boise State player back in 2009. Edwards helped Kelly formulate a plan to get Blount, who was initially suspended for the entire season, back on the football field.

But Cooper’s situation was much different.

“If you suspend him, then what are you going to do when an African-American drops an N-bomb on another African-American?” Edwards said. “Are you going to demand he be suspended? Also, what do you do when someone puts on rap music in the locker room with N-bombs and F-bombs? What you’re going to wind up with is a very short roster.

“If you suspend Riley Cooper and do not suspend that African-American who drops an N-bomb, then it’s not about the N-bomb. It’s about who uses it, and then that opens another can of worms. You’ve got a fence that these people can talk this way and those people can’t. That is not conducive to cohesiveness.”

So Edwards and the Eagles tried to figure out how to get Cooper back into the fold and to minimize this giant distraction. The team needed him. A few days earlier, starting receiver Jeremy Maclin tore his ACL during training camp, leaving the Eagles with limited options at receiver.

Cooper was fined an undisclosed amount by the Eagles and ordered to undergo sensitivity training. Edwards suggested Cooper leave the team for a while to clear his head, and Cooper did, going home to Florida for several days before telling Kelly he was ready to come back. Cooper eventually apologized to every member of his team individually.

While people close to the organization speculated that former coach Andy Reid would’ve been much harsher on Cooper, Edwards said suspending him wouldn’t have helped the team or the situation.

There was a team meeting just after the incident — Cooper wasn’t there — and Kelly opened the floor for the players to say whatever was on their minds. There was tension, former Eagles safety David Sims said, but the majority of talk was positive, focusing on moving on and welcoming Cooper back.

“You know, to some it was a big deal, and to some it wasn’t,” Sims said. “It wasn’t a big deal to me. It’s not the first time I’ve heard a white guy say it.”

A number of various teammates, ex-teammates and coaches were interviewed for this story, and none of them had any memories of Cooper spouting racist comments. He did have a reputation for occasionally being a hothead, yes. In high school, he was suspended for three games for hurling obscenities at an official. He did it as his Clearwater Central Catholic football team was getting manhandled 27-0 by Jesuit High.

Cooper was also a star baseball player — he was drafted by the Philadelphia Phillies in the 15th round coming out of high school — but he never got used to the success-failure ratio in baseball. He couldn’t fathom that failing two of three times at the plate actually meant you were doing well.

He was born in Oklahoma City to an uber-competitive mother who played college soccer and an equally competitive father who’s president of his own realty company. Larry and Monica Cooper moved the family to Clearwater when Riley was 2 and were always active in the athletic lives of Riley and his sister Lindsey, who plays soccer for the University of Florida.

Riley was blessed with a rare combination of size, speed and toughness that made his football coaches giddy and his baseball coaches a little nervous. Cooper hit two grand slams in one game when he was a teenager playing for the Florida Bombers in a select summer baseball league. He also collided head-first with anything that stood in his way.

“He was just a little more assertive and aggressive than kids that age,” said Emilio Fernandez, who coached Cooper on the Bombers. “I totally pin it on the football side of that. A football guy, if he goes 0-for-2, he’s upset and throwing his helmet and moping in the dugout. He’s not handling it the same way as a kid doing only baseball.

“He was a little bit tougher. If he had to run a kid over to get to the bag, he’d do that, and that mindset comes from football, in my opinion. But he was never problematic.”

Cooper was the guy running downfield with his running back, blowing up tacklers. He was the guy who was once challenged to kick a football 15 yards past the field and into some neighboring trees and refused to leave after practice until he did it.

“He got it into the woods,” Jalazo said, “but he couldn’t get it into the woods consistently. Riley wanted to keep doing it until he could kick it in there every time.”

But then there was the temper that got him into trouble. Cooper once punched his fist through the window of a BMW in high school, and the injury kept him out of his senior season of baseball. He was charged with criminal mischief, but, reportedly at the request of the victim, the charges were dropped.

Cooper declined the Phillies’ offer and went to the University of Florida to play football and baseball. His parents wanted him to go to college to mature and grow. After winning two national championships, Cooper was drafted in the fifth round of the 2010 NFL draft by the Eagles, who were hoping to cash in on his immense gifts.

Cooper is a big, strong target who has deceptive speed. He’s a solid blocker and brings attitude to the field. But for the first three seasons of his career, he displayed his vast skills only during practice and couldn’t carry it over to games.

“What he’s doing now is shocking, to be honest with you,” said a longtime NFL executive, who spoke on the condition of anonymity. “To this point, he has shown things he previously wasn’t able to show.”

Is it opportunity? Added motivation to prove himself? Vick said he always saw great potential in Cooper. When the receiver was a rookie, he spent the entire 2010 preseason with Vick, who called him his “go-to guy.” But they never really meshed together on the field. It wasn’t until Vick injured his hamstring in October that Cooper finally started putting up big stats with second-year quarterback Nick Foles.

Cooper caught four passes for a career-high 120 yards against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers in Week 6. He had three touchdowns and another career high with 139 yards three weeks later against the Oakland Raiders.

“Sometimes, you just click with guys, and, sometimes, it takes a lot of time to get comfortable with one another,” said former NFL quarterback Mark Brunell, an ESPN analyst. “It may take a year or two years to really get to the place where there’s a real connection there. Nick and Riley haven’t been together that long, yet they’re able to do some pretty special things. What’s happening in Philly is kind of fun to watch.”

Eagles receiver Jason Avant said Cooper looks up to Foles and the type of person he is.

“Just the way he lives his life,” Avant said of the quarterback. “If they go somewhere, Nick is a little bit different. He doesn’t drink or do certain things. I think he’s a positive influence for him in a lot of different areas.”

Avant said that ever since Cooper was a rookie, he had a reputation for working hard and having a temper that needed to be controlled. In the heat of competition, Avant said, Cooper was “liable to say anything.”

“He had to work his way back with a lot of people,” Avant said, “a lot of black guys on the team. He had to go to some of those guys and let them know his heart about the situation. He did, and I think guys received him.

“I can tell you this, that Riley experiences more racism than anybody. Being a white receiver in the NFL, that’s not a … I’m out there with him. For years, I’ve heard some ridiculous things, that he doesn’t deserve to be out there. That’s happened way before this incident. I don’t want to say it to be a cop-out, but what I’m saying is that him being in the position that he’s in, it happens in this league. So you have to have that mindset to have a merciful heart.”

Winning makes everything easier. At the beginning of the season, Cooper, now 26, was booed at Lincoln Financial Field, but part of that had to do with the fact that he wasn’t producing and the Eagles were struggling. Now when he scores a touchdown, the crowd erupts and cheers.

“I think the city will feel much better if the Eagles win the Super Bowl,” Williams, Philadelphia’s D.A., joked.

Things had come easy for Cooper most of his life. Some people who know him said he gave off an air of entitlement. That attitude appears to be gone.

The security guard who drew Cooper’s ire has never been identified. Contemporary Services Corporation, which helps handle security at the stadium, replied to an interview request but said the Eagles would have to sign off on it. The Eagles have steadfastly said they want to move on from the incident.

So does center Jason Kelce, who was with Cooper at the concert. Kelce concedes it could’ve been a disaster and said in many similar situations, a player wouldn’t have been welcomed back. If Cooper was a jerk, he said, the team probably would’ve turned on him, but they know Cooper’s heart.

“He had to mature or he would’ve been out of here from the get-go,” Kelce said. “I don’t think he had a choice. Right away, the whole front office, the whole city, was on him hard.

“There’s no doubt he handles himself differently in public; he handles himself differently when he’s around people. I think he has to. His whole life changed in a matter of months.”

And so did the Eagles’ fortunes. Edwards, the sports sociologist, is impressed with the team’s success. But he’s just as pleased when he sees a teammate hold out a hand to help Cooper off the ground after he’s made a catch.

“Chemistry is not about liking each other,” Edwards said. “Chemistry is about respecting each other, trusting each other and knowing that you can depend on each other to get their jobs done in what is perhaps the most physically and mentally challenging sport that exists in this country.”

Source link