Authorities say ex-Michigan coach hacked athletes’ photos. Will they get answers?

Hannah didn’t know why the letter from the FBI appeared in her mailbox.

It arrived in November from an FBI field office in Detroit, hundreds of miles from the university in Louisiana where Hannah played basketball. A specialist with the FBI’s Victim Services Division informed Hannah that she had been identified as a possible victim of a federal crime, and assigned her a Victim Identification Number that she could use to track the status of the case.

Hannah, who asked to be identified with a pseudonym to protect her privacy, logged into the FBI’s Victim Notification Service but found little information. She assumed the investigation was related to some kind of online scam, or maybe an attempted identity theft. With little more to go on, she tried not to think about the letter.

A few months later, Hannah received an email from the Department of Justice informing her that charges had been filed against a defendant, Matthew Weiss, in a case of alleged white collar crime. Hannah searched the name and found news stories about a former University of Michigan offensive coordinator accused of hacking the email, social media and cloud storage accounts of thousands of female athletes from across the country and downloading their intimate photos and videos.

“It’s kind of traumatic to know that for years, somebody hacked your account, had your personal information, your passwords,” Hannah said. “This has been going on, and I had no clue.”

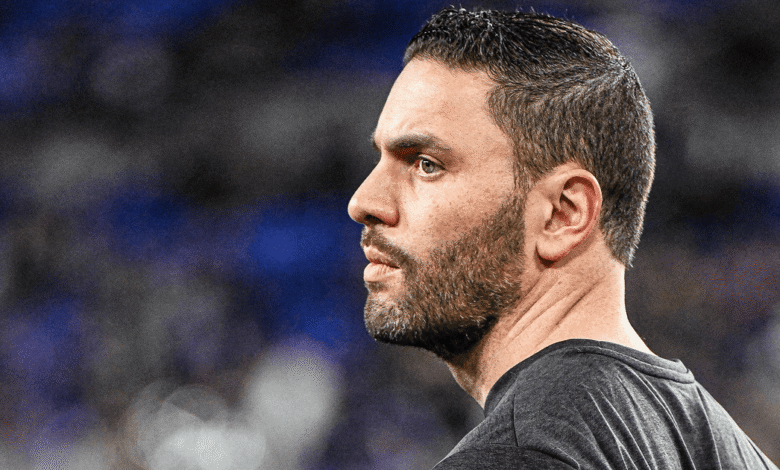

Since learning of the indictment, Hannah has been trying to understand how she was pulled into a web of online hacking activities allegedly perpetrated by a coach who spent 12 years in the NFL and worked for one of the most prestigious programs in college football. Weiss, who was fired from his position at Michigan in 2023, was arraigned in March on 14 counts of unauthorized access to computers and 10 counts of aggravated identity theft, charges that carry a maximum sentence of more than 90 years in prison. He entered a plea of not guilty and was released on $10,000 bond to await trial in November in a federal courthouse in Detroit. Weiss and his lawyer, Doug Mullkoff, have not responded to requests for comment.

According to the indictment, Weiss is accused of accessing databases managed by Keffer Development Services, a third-party vendor, and downloading personally identifiable information and medical data belonging to more than 150,000 athletes. Weiss allegedly used that information to target the online accounts of more than 2,000 athletes like Hannah who have since learned that their personal files may have been recovered in the investigation.

Like most recent college grads, Hannah has more digital accounts than she can keep track of, some of which reused passwords. With no information about which of her accounts might have been compromised, she’s thinking about every digital image and document she stored online and wondering what might have been accessed.

Hannah talked to a former trainer who confirmed that, yes, her school did use Keffer Development Services to store training records. She contacted her school administration but still hasn’t received any official communication — not even a cursory notice informing her of a data breach. The lack of answers for victims has added to the pain, she said. Hannah’s school didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

“I feel like we are kind of being held in the dark,” said Hannah, who was not party to litigation at the time of this interview but has since joined a class-action lawsuit.

In the month since Weiss was indicted, more than a dozen lawsuits have been filed on behalf of women who have reason to believe their personal accounts were compromised. Defendants in those lawsuits include Weiss, Keffer, Michigan and a growing list of schools impacted by the data breach. Plaintiffs are pushing for answers about how their health records and personal information could have been compromised — answers that, to this point, many of their schools have been unable or unwilling to provide.

“Even after finding out all the student-athletes’ personal data had been compromised, the schools didn’t even bother to let us know,” said Sam Roy, a gymnast who competed at Michigan in 2017 and 2018 before retiring and becoming a student coach. “Instead, they’ve stayed silent. They haven’t said anything, not even an apology, not even a notification, nothing.”

Roy said she found out about the hacking allegations by talking to teammates and reading about the case on social media, not from law enforcement or an official communication from the school. She is among 11 plaintiffs, all identified as Jane Does, who filed a class-action lawsuit seeking damages from Weiss, Keffer and Michigan. Nine of those plaintiffs were members of the women’s soccer and gymnastics teams at Michigan, and another was a cheerleader at Michigan’s Dearborn campus. The 11th plaintiff played volleyball at Maryland and Loyola Chicago. Two of the plaintiffs have received victim notices from the Department of Justice, according to the complaint, and attorneys expect additional victims to be identified.

Michigan did not respond to questions about the alleged leak of training records and what guidance, if any, it has offered athletes who might be impacted.

Lawsuits and legal filings have shed light on how Weiss, 42, allegedly hacked personal accounts for years without being detected. The allegations date back to 2015, when Weiss was an assistant coach for the Baltimore Ravens. The majority appear to be concentrated between May 2021 and January 2023, when Weiss was coaching at Michigan.

Weiss didn’t have the stereotypical background for an assistant coach at a big-time program. He was a backup punter at Vanderbilt, where he earned a degree in economics. He got a master’s degree at Stanford and worked as a graduate assistant under Jim Harbaugh, specializing in “opponent breakdowns, tendency and scouting reports,” according to his Stanford bio.

After leaving Stanford, Weiss joined the Ravens as an assistant to coach John Harbaugh and worked his way through the organization as a defensive assistant, linebackers coach, running backs coach and football strategy coordinator, among other roles. Colleagues described him as tech-savvy, capable of designing computer programs to automate tasks that other coaches did by hand. He was known for his ability to spot trends and patterns on film, and a story on the Ravens team site credited him with a film analysis that was used to craft the NFL’s catch rule.

“He’s a really, really smart guy,” John Harbaugh said in the story, which was posted in 2018 and has since been taken down. “He’s a really good football coach. And he has a real eye for these kinds of things.”

Jim Harbaugh hired Weiss as Michigan’s quarterbacks coach in 2021 and promoted him to co-offensive coordinator a year later. Weiss kept a low profile during his two seasons at Michigan, and appeared most comfortable working behind the scenes as a strategist and a numbers guy.

In December 2022, Weiss traveled with the team to the Fiesta Bowl, where Michigan’s unbeaten season ended with an upset loss to TCU in the College Football Playoff on New Year’s Eve. Days later, an entry appeared in Michigan’s campus crime log reporting suspicious computer activity at Schembechler Hall, the Wolverines’ football facility. The suspicious activity had occurred a few days before Christmas, as Michigan was receiving letters of intent from members of its 2023 recruiting class and making final preparations for the national semifinal.

Weiss was placed on administrative leave following the season and fired for cause after he failed to attend a conference to discuss a potential violation of university policy. In a termination letter dated Jan. 20, 2023, the university said it had evidence that Weiss “inappropriately accessed the computer accounts of other individuals.”

In January and February 2023, a district court judge signed 14 warrants to search Weiss’ Ann Arbor home and seize more than a dozen devices, including laptops, iPhones, external hard drives, USB drives and computers in Weiss’ office, the quarterbacks meeting room and the tight ends meeting room. Those warrants remained sealed during the two-year investigation, and the nature of the allegations against Weiss remained a mystery until he was indicted in March.

Jim Harbaugh, now the coach of the Los Angeles Chargers, told reporters at the NFL Annual Meeting in March that he didn’t learn of allegations involving Weiss until after the Fiesta Bowl.

“Shocked,” Harbaugh said, describing his reaction to the indictment. “Completely shocked. Disturbed.”

According to the indictment, Weiss allegedly accessed email accounts belonging to more than 40 Michigan alumni during a three-day period in December 2022, the time of the original report of suspicious computer activity at Schembechler Hall. The U-M privacy office sent a notice to affected individuals in 2023 stating that a “threat actor” exploited a vulnerability in the password-reset function to gain unauthorized access to U-M Google accounts.

The letter, made public as part of ongoing litigation, informed recipients that the U-M cybersecurity team addressed the flaw but could not determine which files might have been accessed. It appears that the initial investigation into hacked email accounts was only the tip of the iceberg, as the investigation uncovered evidence of a years-long hacking scheme with potential victims numbering in the thousands.

Between January 2020 and October 2021, authorities say, Weiss gained access to databases maintained by Keffer Development Services, which markets a platform called the Athletic Trainer System to manage electronic health records. The platform is used by more than 6,500 schools and more than 2 million athletes, according to the company website. Keffer’s website portrays it as a small business that began in the family basement in 1996 and now operates out of a modest building near Grove City, Pa. A company representative declined to comment when reached by phone.

The indictment alleges that Weiss used log-in credentials for trainers and administrators with elevated levels of access and downloaded athletes’ personal information, including encrypted passwords. Lawsuits filed on behalf of former athletes at several schools allege that Keffer provided optional two-factor authentication but did not require it.

The allegations have left potential victims with scores of unanswered questions. Which accounts were hacked, and when? Why weren’t athletes’ medical records more secure? How did the alleged hacking go on as long as it did, and why haven’t schools acknowledged the magnitude of the harm?

“I’m hearing people try to talk about this as just your garden-variety data breach,” said Megan Bonanni, a lawyer representing Roy and other plaintiffs in a class action lawsuit. “One of our missions here is to make sure people understand the trauma that’s associated with this kind of cyber (crime). We’re calling it a form of cyber sexual assault. It is so invasive. It’s a violation, and there’s real injury that’s coming from this.”

Parker Stinar, a lawyer in another class action lawsuit that seeks to represent plaintiffs with claims against Weiss, Keffer and Michigan, asked the court for expedited discovery and a preliminary injunction that would require defendants to turn over documents that could shed light on what they knew about the alleged hacking. The motion argues that potential victims need to know which of their accounts might have been compromised, and what was done with their photos and personal information, so they can take steps to protect themselves.

Michigan knew about the email breach in late 2022, Stinar said, but the school still has not reached out to current and former athletes whose training records could have been impacted.

Michigan and other schools impacted by the alleged hacking haven’t responded to questions about the allegations. More lawsuits are being filed, including complaints on behalf of former athletes at Loyola Chicago, Cal State San Bernardino, High Point University in North Carolina, Simmons University in Massachusetts and Malone University in Ohio.

The revelations in the Weiss case hit hard for Roy and other athletes who have already seen their campuses rocked by multiple scandals. Michigan is three years removed from finalizing a $490 million settlement with survivors of Robert Anderson, a former team doctor accused of abusing hundreds of athletes over four decades prior to his death in 2008.

Roy is a survivor of Larry Nassar, the disgraced Michigan State team doctor serving the equivalent of a life sentence in prison for sexually assaulting female gymnasts. Michigan State reached a $500 million settlement with Nassar survivors in 2018 following a lengthy and traumatic process.

Roy said she felt a familiar sense of betrayal when she learned about the alleged hacking, purportedly carried out by someone hired by her own university. She had started an organization to support athletes impacted by sexual assault and harassment during her time at Michigan.

“It’s incredibly painful to continue to be violated by someone in power,” said Roy. “It’s traumatic enough to start there, but to have it happen time and time again, with another trusted institution, is heartbreaking. Internally, it makes you so upset and just mad. You put (in) so much time and effort — literal blood, sweat, tears, going to practice and putting your best foot forward for the university.”

Roy said she’s disappointed but not surprised by the lack of outreach to potential victims. She said she decided to speak publicly to advocate for other athletes who don’t know where to turn for answers.

“More institutions just look the other way and do the bare minimum to protect themselves rather than taking some sort of accountability,” Roy said. “That’s why I came forward, just for the cycle to stop.”

(Illustration: Will Tullos / The Athletic; Photo: Mark Goldman / Getty Images)

Source link