The NFL’s female coaching surge is here. Just look to the weight room

Sometimes it meant dinner at 10 p.m., but football was just the start of Kansas City Chiefs rookie Ashton Gillotte’s training as a teenager.

Working alongside his trainer, Gillotte competed in Spartan Races, ranked 21st in the Southeast region for CrossFit and qualified for the state championship in weightlifting. As a defensive lineman at Louisville, he earned a spot on The Athletic’s 2022 “Freaks List,” a compilation of the most athletic specimens in college football.

One day, Gillotte brought a group of college teammates to train with his former coach.

“This is crazy,” they said.

“Welcome to my life,” responded Gillotte. “My mom is kind of crazy.”

Veronica Gillotte trained all three of her children — Alexandra, Ashton’s sister, played soccer and tackle football, and brother Devin is a professional MMA fighter. The Chiefs drafted Ashton in the third round (at No. 66) in April.

Having your mom as your strength coach might be unique, but an NFL player working with a female trainer isn’t.

In 2024, the NFL employed 15 full-time female coaches, a 47 percent jump from 2021 and a 1,400 percent increase from 2015.

Opportunities for female coaches in the NFL are especially notable in strength, conditioning and performance departments, where six of those 15 coaches worked. As more women break into coaching and the league at large, the natural pipeline to the weight room is increasingly apparent.

“It’s not surprising because the pipeline was there previously,” said Sam Rapoport, founder of the NFL Women’s Forum. “They could come from the sport that they played. Not too many women play tackle football, but there are many who do.

“It’s an exciting opportunity for the league.”

The pipeline

Most NFL performance staffs comprise four to six people. Their responsibilities touch the entire roster, from keeping healthy players ready for game day to helping injured ones rehab.

The skills of strength and conditioning coaches are uniquely transferable across sports, a key factor in why female coaches have been able to break in at a quicker rate.

Emily Zaler worked for the NBA’s New York Knicks, NFL’s Denver Broncos and WNBA’s New York Liberty before joining the NBA’s Philadelphia 76ers as an assistant strength and conditioning coach/applied sports scientist. She has succeeded over the years by investing in each athlete’s journey.

“There are obvious differences between sports and between athletes’ personalities across different sports and the culture,” Zaler said, “but I think your skill set as a practitioner should remain pretty solid regardless of what environment you’re in.”

Zaler didn’t get involved in professional sports until nine years after she finished undergraduate school at Arizona State. “It’s been a long journey,” she said, reflecting on the absence of women she saw working in the field when she graduated.

In 1990, the New York Jets hired the NFL’s first female strength coach, Lee Brandon; since then, though, representation in these roles has been staggered. In 2018, the Raiders’ Kelsey Martinez was the league’s only female strength and conditioning coach.

It wasn’t until Zaler saw more women breaking into these roles that she felt inspired to go after it herself. With six women working in NFL strength departments entering the 2025 season, aspiring coaches can picture themselves in these roles earlier in their careers. And the improving representation makes strength coaching a unique avenue.

“Positional coaches, like quarterback coaches, wide receiver coaches, (women) are much more limited in numbers,” Rapoport said. “There are very few women each year who are qualified to have an entry-level coaching job in the NFL because we never dreamed about this before. No one was going for it.

“What we’re seeing now is that younger women and girls are looking to take on this career, and they’re excited about it.”

Current female strength and conditioning coaches

College athletics offer wide opportunities to bolster resumes. Haley Roberts trained athletes in seven sports as an assistant at Sam Houston State, ranging from women’s basketball — where weight training is standard — to bowling, where most athletes were international students with no strength training experience.

Each sport helped lay Roberts’ coaching foundation, allowing her to bring a unique perspective to the Las Vegas Raiders’ five-person strength staff.

“I’m not going to appease everyone on the team, but we have someone on staff — because we have a very diverse staff — that will,” Roberts said. “And the opposite: There might be someone on the team that someone can’t get through to, but for whatever reason responds really well to me and the way that I coach.”

Dr. Shawn Arent, a board member for the National Strength and Conditioning Association, said the diversity of backgrounds is one key to a good strength staff. A strong staff should have different perspectives on how to achieve a common goal.

Building trust with athletes is also pivotal, and that comes down to one of the most transferable skills of all: coaching.

“One of the skills that’s a little less measurable,” Arent said, “is your ability to coach and your ability to connect with the athlete. In strength and conditioning, it’s such an important trait.”

Coaches and team executives are also becoming more proactive in expanding their hiring pool to include the top candidates, regardless of gender. One way they meet prospective coaches is through the NFL Women’s Forum, an invite-only event held around the NFL combine that connects women working in college football with head coaches and NFL leadership.

Rapoport, founder of the forum, is clear that the goal was never to simply get women hired. Instead, it was to get the most qualified candidates opportunities they might not have otherwise. Over time, Rapoport said she’s noticed the discourse from team executives looking for candidates shift from “I know a guy” to “I know a person.”

“If you are cutting off half the population of potential candidates, you are losing your opportunity and half of the amazing people that you could potentially hire,” Rapoport said. “We often say with the Women’s Forum, you could plug any underrepresented group in there, and the program works the same.”

Since the event’s inception in 2017, 29 NFL clubs have hired Women’s Forum participants in some capacity. Five of the NFL’s six female strength coaches were participants.

With transferable skills and an increasing awareness of opportunities in the NFL, female strength coaches are more common now than ever before. Arent, who is also the chair of the University of South Carolina’s exercise science department, doesn’t see the trend slowing down. Others don’t either.

“It’s also important that the head coaches … set the expectation that they’re not hiring a female strength coach,” Arent said. “They’re hiring a strength coach who happens to be female.”

The coaches

Maral Javadifar was sitting in her dentist’s chair when she got a call about her dream job.

On the other end was Anthony Piroli, head strength and conditioning coach with the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, inquiring if she would apply for a position on his staff. He wanted to try something new by hiring someone with a physical therapy background — right up Javadifar’s alley.

A few weeks and interviews later, that call turned into a job offer. A birthday present to Javadifar on March 17, 2019.

“The following year, we got Tom Brady for my birthday,” Javadifar laughs. Yes, the Bucs added Brady exactly one year later.

Now the Bucs’ director of rehabilitation and performance, Javadifar admits that once, she didn’t think this was possible. It wasn’t for lack of ambition. But jobs in strength and conditioning were rare enough. And she didn’t see many people who looked like her in professional weight rooms.

In college, she switched from accounting to molecular biology, even though people told her it would be too difficult while playing basketball at D-II Pace University. She persevered, received her doctorate in physical therapy in 2015 and stuck to PT for a few years. But as a former athlete, working in professional sports was always at the back of her mind.

When she got that call, her dream became a reality. And in her second season with the Bucs, Javadifar and assistant defensive line coach Lori Locust became the first female coaches to win a Super Bowl.

“A lot of strength coaches are, I guess, meatheads for lack of better words … trying to lift as much as we can, kind of like a cookie-cutter mode,” Bucs receiver Chris Godwin said in a 2019 NFL documentary. “I think (Javadifar) really understands the broad spectrum of how we as professional athletes need to be developed and need to be worked on.”

Genevieve Humphrey is in her second year as a strength and conditioning assistant with the Carolina Panthers after working as a trainer at Tyndall Air Force Base and Georgia Southern.

Humphrey originally planned to work in the military full-time, but she “fell in love with the sidelines” after getting her first job in football. Working in a male-dominated environment doesn’t intimidate her. Once, she remembers a coach checking in to see if she felt comfortable in the weight room. She laughs now.

A weight room, Humphrey said, feels more like home to her.

“Once guys get over the initial — it’s not shock, but it’s, ‘Oh, there’s a woman who’s my coach.’ — I think they very quickly realize you’re just one of the guys,” Humphrey said.

“They’re like, ‘Wait a second, you belong here just like we do.’”

Even for those who grow up around football, finding their place as a professional can take patience.

Autumn Lockwood was always around her dad’s college football teams as he coached at Notre Dame, Minnesota, Kentucky, West Virginia, Arizona and others. But it wasn’t until she and her dad coached together at UNLV — David as cornerbacks coach and Autumn as a strength and conditioning intern — that she realized the football sidelines were where she wanted to build her career, too.

She just wasn’t sure where to break in full time.

“I remember being upset at the time. I’m like, ‘OK, none of these opportunities are football,’” Lockwood said. “And my dad said, ‘Hey, they might not be there yet, but it doesn’t mean they’re not coming.’”

While Lockwood earned her master’s degree in sports management, she attended the Women’s Forum and met members of the Philadelphia Eagles’ staff. When they hired her in 2022, it was a full-circle moment, with Lockwood returning to her home state.

Lockwood enters her fourth season as a sports performance assistant with the Eagles in 2025. Philadelphia has reached the Super Bowl twice during her tenure, including a win against the Chiefs last season.

“I’m not going to try to make you listen to me or make you respect me,” Lockwood said of her strategy to generate buy-in from players. “I’m just going to show up consistently every single day.

“I think that any athlete, male or female, just appreciates that. They are the best at what they do, so they expect you to be the best too.”

What’s next?

It’s a generalization to say women bring something men don’t to NFL coaching staffs. Rapoport remembers a conversation she had with a general manager after he hired a Women’s Forum participant to his staff. She asked what he observed in the woman’s year on the job.

His answer: It made the men better.

“Prior to having women in here, it was a very artificial environment of all one gender,” Rapoport remembers the GM saying. “But when you bring women in, which better mirrors society as a whole, this is what these guys are used to in their lives. He said it brought down the testosterone levels, in his words, and it made them operate better.”

The evolution of women’s sports is also linked to women’s opportunities in sports. Title IX, the historic legislation that declared discrimination on the basis of sex unconstitutional and transformed opportunities for women in sports, recently passed its 50th anniversary.

“As more and more women had athletic opportunities, they also had those opportunities to go into coaching, to experience the weight room,” Arent said. “Now, some of them have started to gravitate towards ways that they can stay involved in sport.

“Some of what you’re seeing is the long overdue but persistent process to try to make these things more available.”

But there are still steps to take. Every NFL stadium must provide a separate space for female football staff with amenities equivalent to the main locker room, but Roberts, the Raiders’ staffer, remembers instances in college where there wasn’t a designated women’s locker room. At road games, she would have to change quickly before the team arrived or go across the field to the women’s bathroom, sometimes eating into valuable time she needed to help with warmups or halftime recovery.

Leadership is another touchpoint. Javadifar is the NFL’s only female strength and conditioning coach currently in a director role. It’s an important distinction, but Javadifar is quick to deflect bragging rights to women who came before her.

“When people say you’re one of the first, I don’t actually believe that,” Javadifar said. “There have been plenty of successful women who have been in the world of performance that have done a heck of a job to even start creating that path.

“I truly dislike the whole notion of being a female coach. … I don’t want to be identified for what I am, but what I bring to the table.”

Rapoport said she’s often asked about the timeline for the NFL’s first female head coach or first offensive or defensive coordinator. That’s not her focus, she said.

“We like to celebrate firsts, but we quickly move on because we don’t want to fixate on it and get too excited about it,” Rapoport said. “Like any male coach, a woman coach has to prove herself.

“Where we’re focused is the numbers at the entry-level, in college and high school football, and a lot less at the top.”

But the ultimate goal, as each coach mentioned, is getting to a point where female coaches are not an outlier but the norm. When having a woman in the weight room or on the sidelines becomes a non-story. And when aspiring professionals set their eyes on role models and opportunities in the league, earlier.

In many ways, the progress is already clear.

“In my mind, it wasn’t ever impossible to work in the NFL,” Roberts said. “No one ever told me like, ‘Oh, that’s never gonna happen.’”

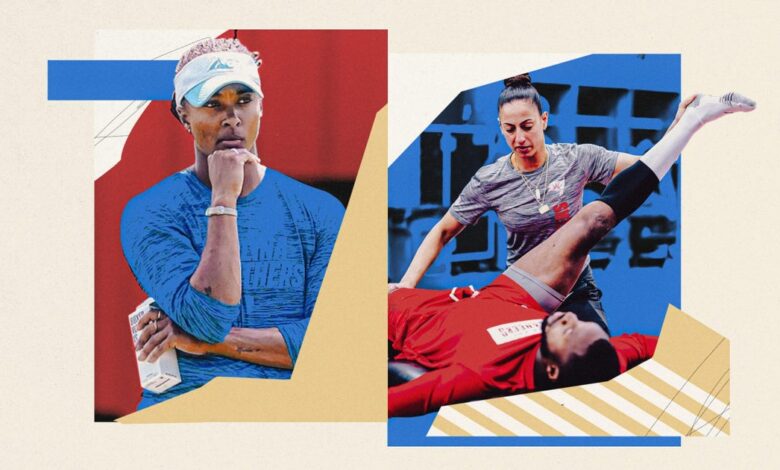

(Illustration: Kelsea Petersen / The Athletic; photos courtesy of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers and Carolina Panthers)

Source link