How the tennis calendar and tournament schedule works – and why players and fans love to hate it

This article is part of the launch of extended tennis coverage on The Athletic, which will go beyond the baseline to bring you the biggest stories on and off the court. To follow the tennis vertical, click here.

The fight for control of professional tennis that has consumed leaders and top players for the past year has forced the sport to confront a question as old as the modern game:Is professional tennis a sport of the Western elite, or is it a global game for the masses?There is a pro match taking place somewhere in the world every day for 11 months each year. It makes tennis a worldwide phenomenon, with fanatical support all across the globe, and a staggering range of tournaments.

It also makes it a worldwide phenomenon with minimal rest, confusing scheduling, and unrelenting demands on players’ physical and mental health.

It is a blessing. It is a curse.

“We play the longest schedule in professional sports,” Novak Djokovic, the top men’s player of the modern era, said with varying amounts of pride and regret earlier this year.

That schedule, what it demands of players, who gets to control and collect the money it produces, and what tennis was, is and strives to become, are at the heart of the current fight among the most powerful entities in the sport.

The tennis schedule is what started this chapter of a decades-long struggle to bring more order to this fractured sport. It will be at the center of the peace treaty that the four Grand Slam events and ATP and WTA tours will eventually agree to, which they say is slowly being discussed, pondered and battled over in weekly teleconferences.

There will likely be some kind of middle ground between a shortish schedule in a handful of world capitals — a Formula 1 of tennis, if you will — and the endless string of tournaments, competitions and exhibitions across the world that exhausts and confuses players and fans alike, but also gives tennis a potential reach and depth of which other sports, except perhaps soccer, can only dream.

The Grand Slam plan is for a premium tour that would include 10 other events, alongside their quartet, designed for roughly the top 100 players. The tours’ plan represents the interests of more than 100 tournaments all over the world.

They are already lesser in ranking points; under this proposal, they would become lesser existentially and practically, too.The players, who come from places as different as Kazakhstan and Kansas, are caught in the middle, with neither plan offering a vision for their main problems: playing too much tennis, and not collecting a large enough share of the riches.

“Other sports have done a better job of this,” said Robby Sikka, a physician who has worked with multiple pro sports teams and recently became the first medical director of the Professional Tennis Players Association.

“We have to optimize individual players’ health with the schedule. Other leagues have a mandatory number of days off per month, and we are talking about true off days.”

Andy Murray played an ATP 250 in Geneva to come back from injury before the French Open (Fabrice Coffrini/AFP via Getty Images)

Where everyone agrees? The two initial plans don’t work.

“No one would advocate that playing just the Grand Slams is a good idea, or (that) having tennis for 50 weeks of the year is a good model,” said Phil de Picciotto, the chief executive and founder of Octagon, a sports marketing firm with deep roots in professional tennis, during a recent interview.

Octagon, like its competitor, the sports and media conglomerate IMG, has owned and operated tournaments and represents players. That would be considered a conflict in most sports and businesses but it is endemic to tennis, and has had De Picciotto involved in plenty of meetings attempting to resolve the current fracas.

“You need both,” he said. “You need certain peaks in the calendar, where the entire tennis universe meets and the world recognizes those brand names globally as major happenings in the world of sport. And then one cannot forget the absolutely essential requirement that there be a developmental runway to bring talent around the world, because you want the most people playing tennis, and to have the opportunity to consume it, with enough events spread out throughout the world with top quality so they have a chance to interact on a live basis.

“It’s the blend that is critically important.”

Then de Piccioto explained what has had everyone in the game on edge for nearly a year — with lawyers on speed dial, just in case: “It is not an easy problem to solve and getting people of such different backgrounds and interests to move to aligned ground has proven impossible.”

IMG represents many players, including rising star Mirra Andreeva (Clive Brunskill/Getty Images)

The global blend he envisions is what drives the sport’s economy, in good ways and bad.

In a world where sports media is all about streaming, tennis and the various networks it has spawned offer something practically no other sport can — live competition (of varying degrees of importance) at some point on nearly every day of the year. The current schedule is perfect for someone such as Ken Solomon, the chief executive of the Tennis Channel, the California-based media company with a growing international presence.

In a perfect world, tennis would have one exclusive media outlet, and a collection of premium worldwide sponsors with a presence at every tournament and the opportunity to reach a wealthy collection of fans all year with a single deal.

In the real world, all those events cannibalize each other. They compete for sponsors and media deals, driving down prices. A company that wants to reach fans at every tournament often has to sign separate deals with nearly everyone.

The system simply doesn’t work. But the plan for how to fix it has so far brought more problems than solutions.

A little more than two months after a showdown in Indian Wells, California, that left both the Grand Slams and the tours bruised, the leaders of the rival camps are beginning to share the belief they might have come out a little too aggressively.Andrea Gaudenzi, a former tour pro and now chairman of the ATP Tour, views himself as something of a transformational leader, someone who can unite the alphabet soup of ruling bodies under one vision.

He has been leading the tours’ efforts to gain a cultural relevance that is closer to that of the Grand Slams. It was his push for a new, top-level tournament in early January, bankrolled by $1billion from Saudi Arabia, that set off this latest internecine strife. The Grand Slams, initially led by Tennis Australia, moved to protect their ground. Making it clear they would not be trifled with, they essentially tried to cleave the biggest and best-known tournaments from the men’s and women’s circuits to create that premium tour.

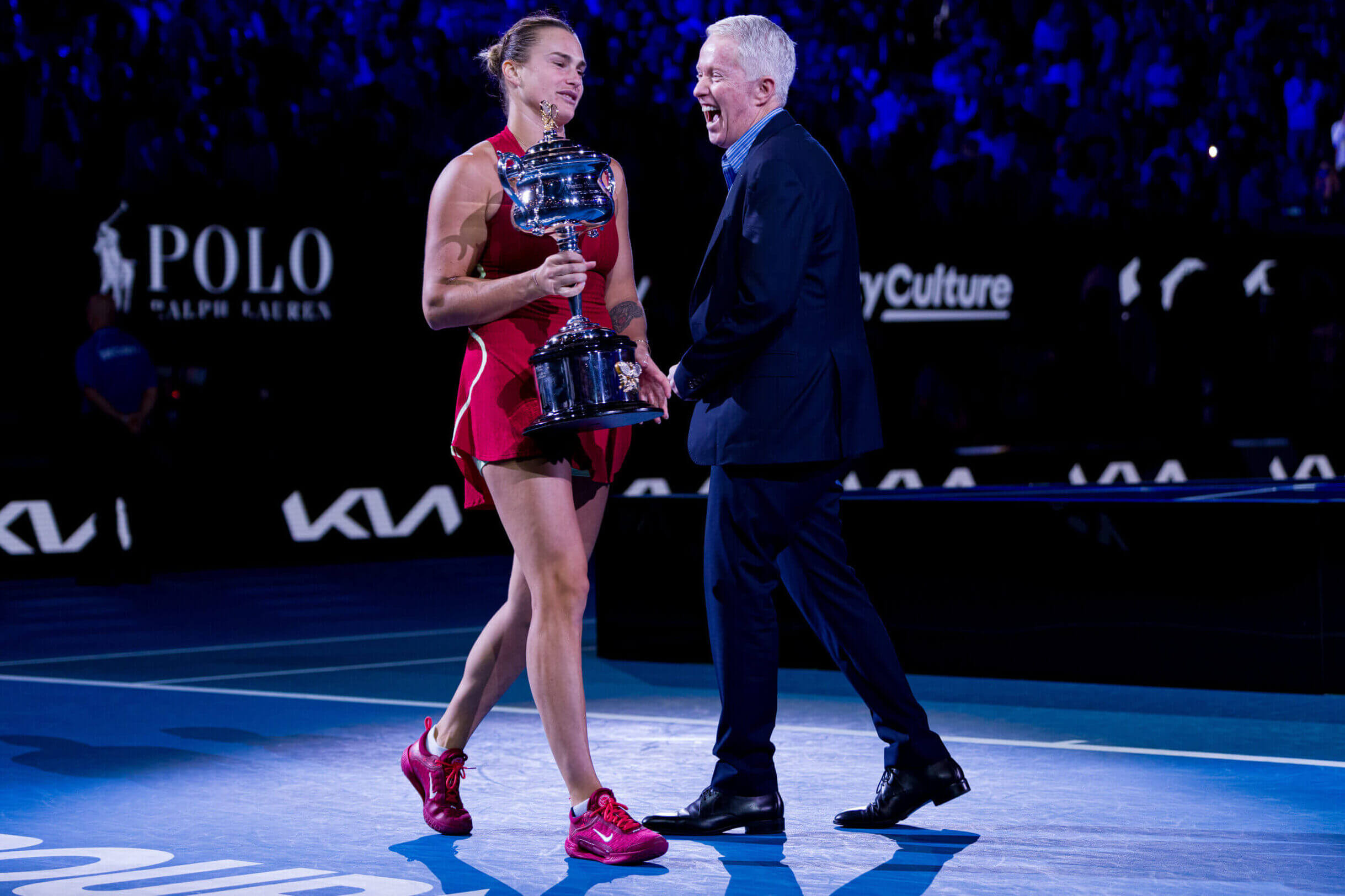

Australian Open executive Craig Tiley with this year’s women’s champion, Aryna Sabalenka (Andy Cheung/Getty Images)

In March, Craig Tiley, chief executive of Tennis Australia, presented his counterparts with a proposed calendar for his version of the future — the four Grand Slams and 10 other two-week blocks for tournaments and locations to be named later. Everyone knew the Grand Slams were targeting the so-called Masters 1000 events in Doha, Dubai, Indian Wells, Miami, Monte Carlo, Madrid, Rome, Canada, Cincinnati, Beijing, Shanghai and Paris.

Leaders of the tours and owners of the scores of other tournaments across the globe whose events would be reduced to qualifying competitions for the big show were irate. Under the proposal, their sponsorship and media deals would likely collapse, the event licenses they had shelled out millions for becoming worth a fraction of what they had paid.

Tiley and the leaders of the other Grand Slams have since come to accept that their proposal may have been an overreach, reeking of Anglo-American cultural elitism.

It would have meant top-level professional tennis in Asia, the planet’s largest and most populous continent, would amount to two weeks in China. There would be zero top-level tennis in South America, Africa and all the rest of Asia. There would be no tennis in Germany, the world’s third-largest economy, or in Japan, its fourth. Locally beloved events in Argentina and Brazil, Portugal and the Netherlands? Sorry.

“You can’t market a global sport with 14 tournaments,” according to one tournament owner, who participated in meetings and spoke on condition of anonymity to describe the private discussions.

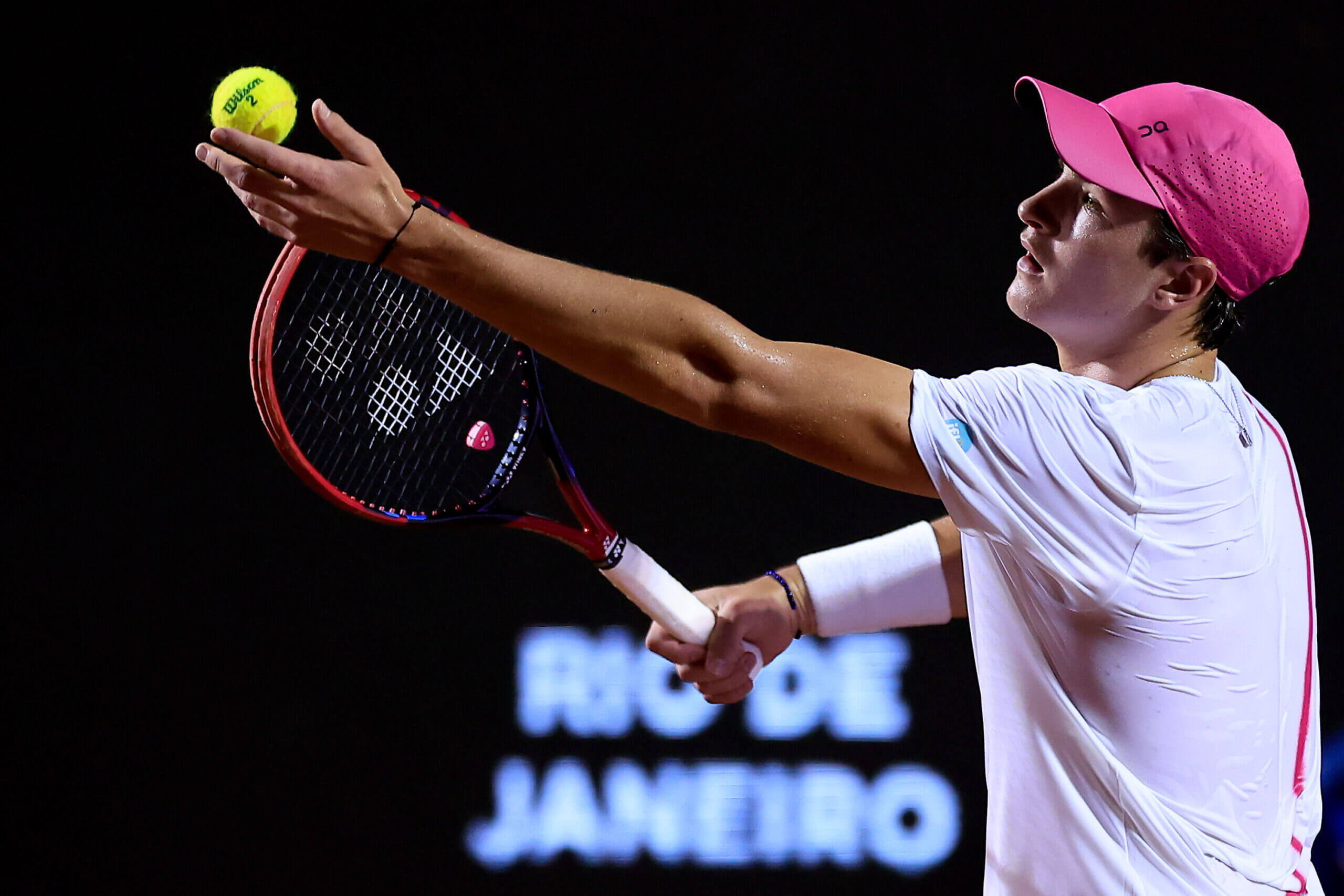

Andy Murray, the three-time Grand Slam champion who has become a kind of tennis wise man, said the sport should go in the opposite direction, with a series of top events in South America, which has some of its loudest and most enthusiastic fans. That continent has also produced some of the sport’s most beloved stars, including Juan Martin Del Potro and Gabriela Sabatini. And here comes 17-year-old Joao Fonseca of Brazil, one of the game’s hot young things.

Joao Fonseca serving against Cristian Garin, of Chile, in Brazil (Buda Mendes/Getty Images)

Both sides have now begun to compromise. Gaudenzi has grown less insistent the season should kick off with that new top-level tournament, likely in Saudi Arabia, ahead of the Australian Open later in January. He’s now open to scheduling it anytime during the first two months of the year.

He, and the Grand Slam leaders, have agreed that there has to be a better way, one that would protect the Grand Slam swings, keep the tours relevant and give players what they really want, which is more money, a little more down-time during the season and up to eight weeks off at the end of it.

The problem? The earth currently takes 52-and-a-half weeks to circle the sun. There is no sign that the year will expand to 60 weeks, at least not anytime soon.

Even before this new chapter in the battle to fix tennis opened, the players were finding themselves moved around like chess pieces in a sport whose fame and appeal they drive.

Gaudenzi wanted to build the tours’ power by investing in those Masters 1000s. They are the tours’ most lucrative events. So, they expanded them, producing tens of millions of dollars in additional revenue, increased prize money, and more eyeballs on tennis. Fans have gobbled up the tickets for the additional days.

The Italian Open in Rome was a one-week tournament; now it lasts nearly two. Madrid expanded to 12 days from nine. Next year, the events in Cincinnati and Canada will expand to 12 days from one week.

Daria Kastakina serves at the expanded Masters 1000 in Madrid (Julian Finney/Getty Images)

Tour officials say that with increased prize money comes increased tennis. Women’s prize money will grow by $400million during the next 10 years, in part because of these changes. Officials have also argued that the longer schedules offer additional off days between matches, so there’s more time for recovery. Best of both worlds.

Some players (Danielle Collins, Aryna Sabalenka) agree. Most of them don’t. Top players say that even these events wear them down, in a schedule so punishing that true rest is barely possible.

Sikka, the players’ medical director, isn’t convinced that these rest days are really rest. Longer tournaments mean more time away, and less time for the kind of practice and training necessary to survive the season. Exhaustion from everything off-court — travel, stress, waiting — increases the risk of illness and injury on it.

Danielle Collins with opponent Anna Blinkova, who retired injured in Rome (Mike Hewitt/Getty Images)

Jannik Sinner even injured his hip in a weight-training session during the Madrid Open, which is not something that top players used to do in the middle of big tournaments.

“Rest days are not all created equal,” Sikka said. “Giving off days in the middle of a tournament doesn’t really help.”

“We don’t have time to do physical work,” said Alexander Zverev, a member of the ATP Player Council. “We don’t have time to focus on our tennis games.”

These newly-expanded tournaments also further divide the top of the rankings from the rest. Lower-placed players benefit because the larger draws give them more opportunities to play on bigger stages, but they are far rougher for the top players who go deeper into most events.

Iga Swiatek, the women’s world No 1, said many players feel like they were informed of the decision to expand the events and make an additional women’s tournament mandatory without being actively consulted about it. There is a women’s Players Council, but there are no active players who sit on the WTA board. They are too busy actually playing for that. Tour officials say the players need to work through their board representatives.

“We had a couple of situations where it would be nice if the WTA took a lesson from them, like deciding kind of behind our backs sometimes about the changes in the amount of mandatory tournaments,” Swiatek said. “That was pretty harsh for us, because these are literally the topics that influence our lives and our, and our recovery time.”

Women’s world No 4 Elena Rybakina agrees.

“These tournaments, which became so long, it’s not very helpful,” she said. “To stay in one place for almost two weeks, and it’s not like here you finish and you go rest. You go and you play another mandatory one. That’s definitely not making it easy.”

During the Madrid Open, Rybakina played compatriot Yulia Putintseva. She found herself down 5-2 and two match points in the third set. She found herself thinking it wouldn’t be so bad to lose.

“You are so tired that at 5-2, you’re just (like), ‘OK, if I’m going to lose, I’m going to have some vacation because the next tournament is coming’,” she said.

She didn’t get the vacation; she rallied to win the set, 7-5.

The next week, Rybakina was the defending champion at the Italian Open.

She pulled out with illness before her first match.

(Illustration: Dan Goldfarb for The Athletic)