Buccaneers coach Raheem Morris uses rugged past as motivation in NFL – New York Daily News

An unspoken message gets relayed to anyone who tours the streets of Irvington, N.J., a silent yet not-so-subtle slogan that is broadcast to outsiders and citizens alike: This isn’t a place for the faint of character, or the meek.

On each block and each street corner, you are immersed in the reality of an impoverished community. Steel-framed bars guard the windows of many homes – the ones that are still standing, at least. Others have been condemned, boarded up and left to crumble, or worse, transformed into crack houses.

White barricades line the intersections of the residential areas with a glum duality in their purpose: to deter individuals who steal cars and attempt to jet from the scene, and to prevent the deaths of innocent bystanders and motorists caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

The pyschological residue of the drugs, gangs and violence that litter the city like a minefield is the assumption that it is impossible to break free from Irvington’s hold.

Raheem Morris never looked at it that way.

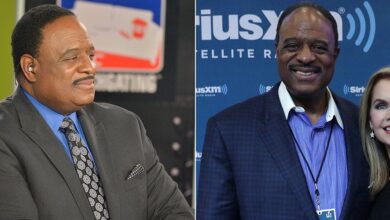

The 33-year-old first-year head coach of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers saw Irvington’s pitfalls and used them as a catalyst to stay on the straight and narrow, wearing his hometown’s rugged character like a tattoo.

“I believe it’s in the individual,” Morris says.”I chose to be around the positive people in Irvington. I got lucky enough to get friends that weren’t going to get into that much trouble. We got into our fights here and there, but there was nothing around in place for me to be really negative. If you can do that as an individual, you can grow up anywhere.”

Morris knew from a young age that the culture of Irvington, a town just west of Newark, could hit you harder than a safety laying out a wide receiver. He met the challenge head on.

So when the Tampa Bay Buccaneers named Morris head coach on Jan. 17, making him the youngest in the NFL, it validated a journey that was as astounding as it was atypical. It also made Morris a symbol of how to overcome adversity for a township entrenched in poverty and violence.

“I have no ill feeling toward Irvington or Newark,” Morris says. “Those are the places I’m from. Maybe I had to be a little more mentally tough to get out of those places, but you have to be more of an independent person, more of a leader than a follower.”

Morris clung to the right crowd and one of the people in his inner circle, Eugene Robinson, who is still one of his best friends, can attest to the iconic stature Morris now holds in Irvington, where the two spent their formative years together.

“When you have someone who made it as far as Raheem, people are so happy for him because they know what he went through,” Robinson says. “They know what he went through here. The whole township is proud of him.”

Robinson, 34, is also witness to Irvington’s dark side – past and present. As the varsity basketball coach and an English teacher at Irvington High School, which he and Morris both attended, Robinson tries to be a case-in-point example for the students that there can be a life past Irvington.

“Some of these kids don’t have clothes,” Robinson says. “We as coaches provide them with stuff like that sometimes. So when you’re growing up in it, it’s hard to believe that you can be all you can be. It takes a real strong person to fight and believe that they can make it.”

Yet sometimes circumstances intervene. Morris came from a household that had both parents and made it out. But even when all the pieces are in the right place, there can be a different ending. Robinson, in his nine years as basketball coach at Irvington, has witnessed senseless tragedy.

“I’ve been coaching here nine years and I’ve buried two of my players – one at 17 and one at 18,” says Robinson, who says that each was a victim of wrong place, wrong time. “It happens in a lot of inner cities, but what I like to bring to people’s attention is that these kids grow up thinking that’s normal just because that’s everyday life for them. These kids are numb to it.”

Morris never suffered that fate. He and Robinson were engulfed in athletics, and each credits being “too busy with sports” as a big reason they stayed off the streets.

“I was more interested in being positive, being successful and I didn’t want to disappoint my parents,” Morris says. “They mean the world to me. I know if I got into trouble the disappointment for them would be unbearable.”

And when Morris approached the precipice of trouble, his parents cracked the whip. A bad report card kept him off the football team his sophomore year at Irvington – even though a 2.0 GPA was good enough to keep him eligible, it wasn’t up to snuff for his parents. He wasn’t suiting up for his high school team, period. And it didn’t matter that in Irvington positive distractions kept you alive.

“They told me that wasn’t my best self and they weren’t going to let me play,” Morris says. “I didn’t touch a football in high school until I was a junior. It was a great lesson I needed to learn before college. I was mentally tough enough to get through it.”

Intended as punishment, Morris’ ban turned out to be brilliance. It forced him to start watching the game, sculpting an analytical eye. Robinson recalls not seeing Morris around as much that year.

“His focus was that he needed to get right so he can play sports next year,” Robinson says. “That incident alone makes you wonder where Raheem would be today if his parents had let him slip up. They never had another problem out of Raheem after that.”

Morris was incredulous at his parents’ decision, but to keep himself focused, he began keeping statistics for the Pop Warner football team his dad coached and kept tabs on Irvington’s squad. He lifted his grades and hit the books – and eventually hit opponents.

During the year without sports, Morris kept himself out of trouble as much as possible. Though he and Robinson cop to some minor missteps, Morris credits his family for keeping him in line: His grandmother, mother and father helped him keep statistics rather than let him become one.

“It makes you tougher,” Morris says. “You can’t walk around and not see it or live in a fairy tale land. It’s definitely not that type of mentality. You have to stay positive.”

Morris figured out who the “imitation tough guys” were, he says, and stayed away from them. “They become tough guys because of who they hang out with. I didn’t have to be a tough guy who followed people.”

Eventually, Morris began thinking about the next step. He knew college was his ticket out of Irvington, and eventually decided on Hofstra, a Divison I-AA school in Hempstead, L.I., and played defensive back there from 1994-97, often in the shadow of safety Lance Schulters, who would spend nine seasons in the NFL.

“When I played football I did a lot of studying tape,” Morris say. “I could look at Lance at any given time and tell him exactly what he should be doing. I could call the defense.”

Never short for words, Morris played the way he talked – with tenacity. Neither opponents nor teammates were spared his wrath.

“He was never tired and never took a play off,” says Adam Brown, who played and coached with Morris at Hofstra. “He never ever closed his mouth, either.”

Joe Gardi, head coach at Hofstra from 1990-2005, recalled seeing a coach-in-waiting.

“He was just an outstanding kid with a great personality,” Gardi says. “He was as close to me as anyone I’ve ever recruited. I had a special feeling about him. Even if he never became a coach in the pros, I was especially proud of him. He never gave me a bit of problems off the field. He was an outstanding citizen.”

When Morris was finished playing, Gardi hired him as a graduate assistant in 1998. Some days, Morris watched hours of film before he even saw the sun.

“He’s so technical,” Brown says. “He could talk about the first three back-pedals of a defensive back for three hours. He may bore you to death, but he’s about fundamentals.”

Morris parlayed that into a job at Cornell in 1999, then returned to Hofstra in 2000 as defensive backs coach. Then fate was taking a leisurely jog through the Jets‘ practice bubble at Hofstra one morning in the form of Herman Edwards, Gang Green’s head coach at the time. Gardi flagged Edwards down and told him to watch Morris.

“That was the luckiest thing that could have ever happened to me,” Morris says.

When Edwards asked Morris what he’d be doing that summer, Morris’ reply – “Whatever you would like” – landed him the defensive minority internship with the Jets. He spent the summer shadowing the Jets’ defensive quality control coach.

Sure enough, when Tony Dungy was fired by the Bucs after the 2001 season and replaced by Jon Gruden, Edwards gushed about Morris to defensive coordinator Monte Kiffin.

“That’s where the story began,” says Morris, who was hired as Tampa’s defensive quality control coach, or as he puts it, a glorified graduate assistant.

For Morris, 2002 was a blur. He made Kiffin equal parts coach and teacher that season, harvesting as much as he could. Defensive backs coach Mike Tomlin, who coached the Steelers to the Super Bowl last season, was also a great influence on Morris.

“We won the Super Bowl and that was a great deal,” Morris says of the Bucs’ 2003 championship. “You get a ring, a big bonus and everything else that comes with it.”

Morris spent 2003-05 as a Tampa assistant, then went on a limb and took the defensive coordinator gig at Kansas State in 2006.

“It was my show,” says Morris, who returned to the Bucs as secondary coach in 2007 when Tomlin went to Pittsburgh. “But no disrespect to college football, it just wasn’t the NFL When you’re in pro football it is your life and that was what I loved and missed.”

After Gruden’s firing and the departure of Kiffin to coach with son Lane at the University of Tennessee, last January Morris once again found himself in the right place at the right time.

“I always thought Raheem would be a head coach,” says Brown, now a head coach at West Hempstead High School on Long Island. “Now I didn’t think he’d do it in the NFL at 32, but knowing him, he’s absolutely ready.”

Now, Morris will try to turn around a Buccaneers team (0-2) that plays the Giants today and has lost much of its veteran leadership in linebacker Derrick Brooks, who was cut in February. Morris, however, pays no mind to his age or critics.

“He has that Irvington attitude like nothing can stop him and that’s because of where we grew up and how he grew up,” Robinson says.

Morris is focused on the task at hand. “Right now I have to go out and lead these men not where they want to go but where they need to go,” he says. “That’s my job.”

Source link