Oliver Stone Depicts Football as a War

Football is not for the faint of heart in America. Whether at the high school, collegiate, or professional level, the sport has transcended beyond a game and established itself as a religious following among the public. In order to adapt the equally chaotic and romantic sentiment of football for the big screen, few directors were more equipped in 1999 than Oliver Stone. The two-time Academy Award-winner for Best Director made his name off of capturing the gravity of the nation’s most topical issues: the humane impacts of the Vietnam War with Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July, the murky truth behind the John F. Kennedy assassination with JFK, and the origins of violent tendencies and its media exploitation with Natural Born Killers. At the turn of the century, Stone brought his style of maximalist MTV-like editing, integration of various film reels, his thematic penchants as a provocateur, and an overwrought sense of earnestness to Any Given Sunday, a football movie where football is a matter of life and death.

Stone’s inspiration for Any Given Sunday, the gut-wrenching depiction of war, Saving Private Ryan, is all that’s necessary to know regarding his interpretation of football. In the film’s DVD commentary, he cites that Steven Spielberg‘s use of disorienting camera shaking was used as the basis for shooting the football games. It is evident from the get-go that Stone views football like a combat battlefield. The violent nature of tackles is ramped up to a ludicrous degree, with players suffering through pain as if they were inflicted by bullets. Whatever team wins this game is ostensibly secondary compared to the struggle for survival.

Despite Stone’s best efforts, there is a second-rate feeling to the direction of the unbridled brutality of football compared to the execution of the horrors of war in Private Ryan. Stone pushes too hard for shock value when directing the game sequences. During the climactic playoff game of the Miami Sharks, the film’s team of focus, a defensive player on the opposing team loses an eyeball. The film’s shock value plays like a rebellion against the NFL, which refused to lend its team rights or cooperate with production. Because of this, Any Given Sunday presents itself as an unflinching look at the real savagery on the field that the NFL doesn’t want the public to see.

Oliver Stone’s Style of Maximalism in ‘Any Given Sunday’

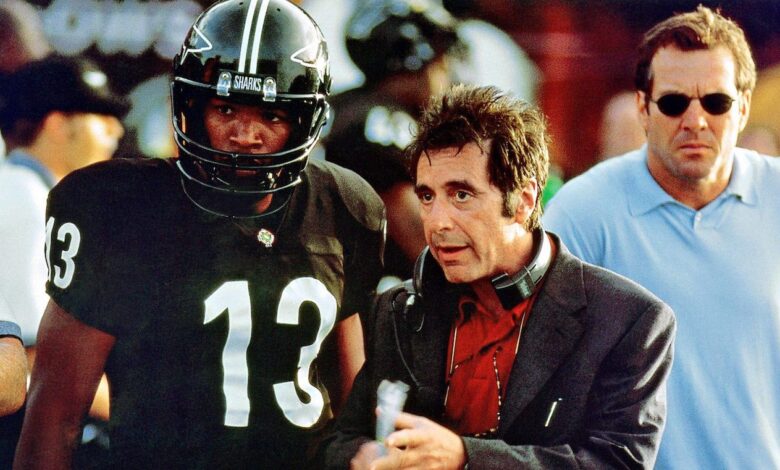

While this film is reaching for a message about football as a solemn life and death activity, let it be unmistaken that Any Given Sunday is immensely over-the-top and cartoonish at every level. It’s difficult to take the credence of this film as a gritty and grounded depiction of life in professional football considering that there is a scene involving the Sharks’ defensive captain, Luther “Shark” Lavay (played by NFL legend Lawrence Taylor), where he takes a chainsaw and cuts an SUV in half. In another instance, a rowdy player, amid a victory, throws a live alligator in the locker room shower in the presence of his teammates. Playing into the perceived stereotype of the cocky black quarterback, third-stringer Willie Beamen (Jamie Foxx) records a hip-hop track and music video after his first win. All in all, Any Given Sunday is about as subtle as a Lawrence Taylor blindside sack. The role of Miami Sharks Head Coach Tony D’amato was practically conceived for late ’90s Al Pacino. While his engaging and sturdy performance is par for the course, he only heightens the film’s sensationalism with his fiery energy. The characters of Beaman, team owner Christina Pagniacci (Cameron Diaz), and Dr. Harvey Mandrake (James Woods) all fall into shallow characterization. Each character is emblematic of different thematic ideas that the film wants to be about (an underdog story, capitalism undermining the sport, immoral treatment of players surrounding concussions) but since Stone is unable to pick a lane, every direction of the story is thrown in at once. On the flip side, Stone’s examinations of the varying facets of professional football, even if they’re occasionally half-baked, exhibit the importance of football and the powerful forces that make up its palace intrigue.

For as demented as the film behaves, the earnestness of Any Given Sunday is in the spirit of the passionate commitment that presides among football players, coaches, and fanbases. While not executed as effectively as in his masterpiece, JFK, Stone maintains some balance of the cocaine-induced depravity of the eyeball-popping and chainsawing with a romanticism of the sport. The skirmish on the gridiron is made to feel like life-or-death naturally, despite Stone’s ham-fisted allusions to football players as modern-day gladiators (no joke, Coach D’Amato is watching Ben-Hur during a pivotal scene with Beamen where they discuss the importance of quarterbacks as leaders on the battlefield). On the DVD commentary, the director likened the livelihood of a quarterback to a military general and the Sharks’ front office to a presidential administration. This kinship to Stone’s previous works, such as Platoon and Nixon, lends the film a sense of grandness. In addition to the often-bloated military allusions, religion is woven into the overarching text, as seen with the priest who leads a prayer with the team in the locker room at halftime and the Dallas team that the Sharks face in the playoffs whose helmets feature a cross-shaped figure. Beamen states to D’Amato that his mother does not attend her son’s games because she believes Sunday is exclusively for the church.

Many Americans wrestle with their conscience regarding their relationship with football. They are intellectually cognizant of the barbarity of the sport and the monetary greed of NFL team owners and the league office that compromises player safety, but we keep watching every single week throughout the fall and early winter. This complex is evident in the devotion that the players of Any Given Sunday have to put their health and well-being on the line for a game. The film was prescient to the concussion crisis that has consumed much of the discourse surrounding football. “Shark” Lavay, who suffered numerous concussions, is so determined to go out on the field, he signs a paralysis waiver from the team’s medical staff in order to play. Longtime Sharks quarterback, Jack “Cap” Rooney (Dennis Quaid), experiences significant health woes after years of injuries, citing that he “can’t even hold a spoon.” Yet, despite their physical agony, they are drawn to return to the football field at all costs. With the help of Stone’s experience of directing weighty dramatic stakes, the film creates a simultaneously operatic and tragic depiction of the sport.

The legacy of Any Given Sunday is mainly remembered for its pregame locker room speech orated by Coach D’Amato, referred to shorthand as the “Inches Speech.” While most of the film is appreciated with a strain of irony, viewing at times as “so bad, it’s good,” the speech, supposedly based on a real address given by former Cleveland Browns coach Marty Schottenheimer, is a legitimately moving and awe-inspiring piece of writing, directing, musical scoring, and acting. Pacino was born to rattle off this epic sermon that signifies the power of the sport and unifies a fractured squad. D’Amato reveals his insecurities by expressing his anxieties around aging and how life gradually took things away from him. As he puts it, he “chased off anyone who’s ever loved” him and “can’t stand the face” he sees in the mirror. However, if there is any fight left in him, he wants to channel it through the gridiron. Even if it can’t absolve his demons, football gives him life. Every inch of something can be fought for and not be stripped away from the natural progression of life. This is true on any given Sunday.

Source link